Activity 8.7.1. Comparisons to Bound Partial Sums.

This activity is mostly going to be thinking about proof mechanisms, and so it might be helpful to review Activity 8.4.1 Integrals and Infinite Series. If you want to see more, then the proof of Integral Test will provide some further details on why the inequalities we built were useful.

(a)

In the Integral Test, how did we guarantee that our sequence of partial sums was monotonic?

(b)

How did we know that, as long as the corresponding integral converged, then our sequence of partial sums was bounded?

(c)

How did we know that, as long as our integral diverged, then our sequence of partial sums had to diverge as well?

(d)

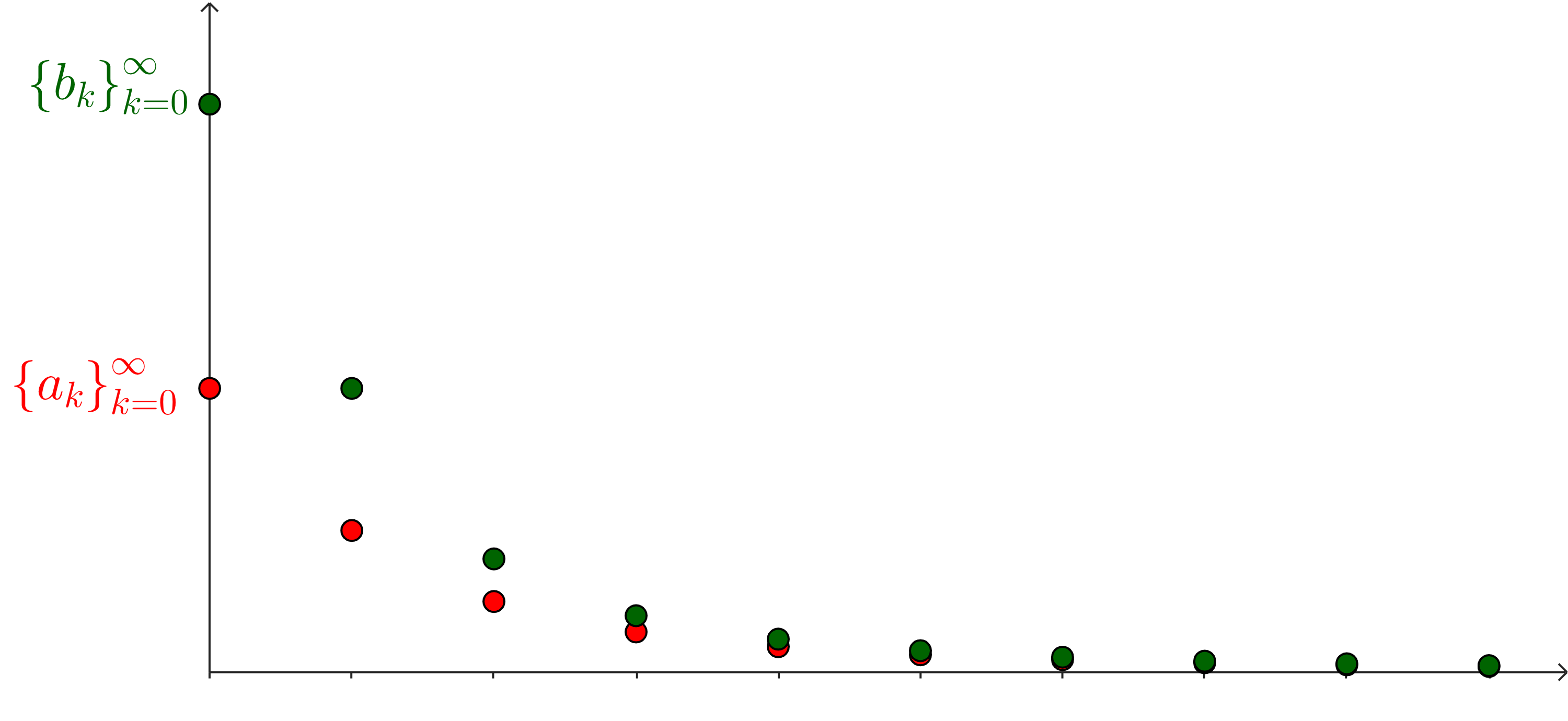

What happens if we swap out the integral we’re connecting our series to with a different series?

For these inequalities to be useful, what do we need to be true?

Hint 1.

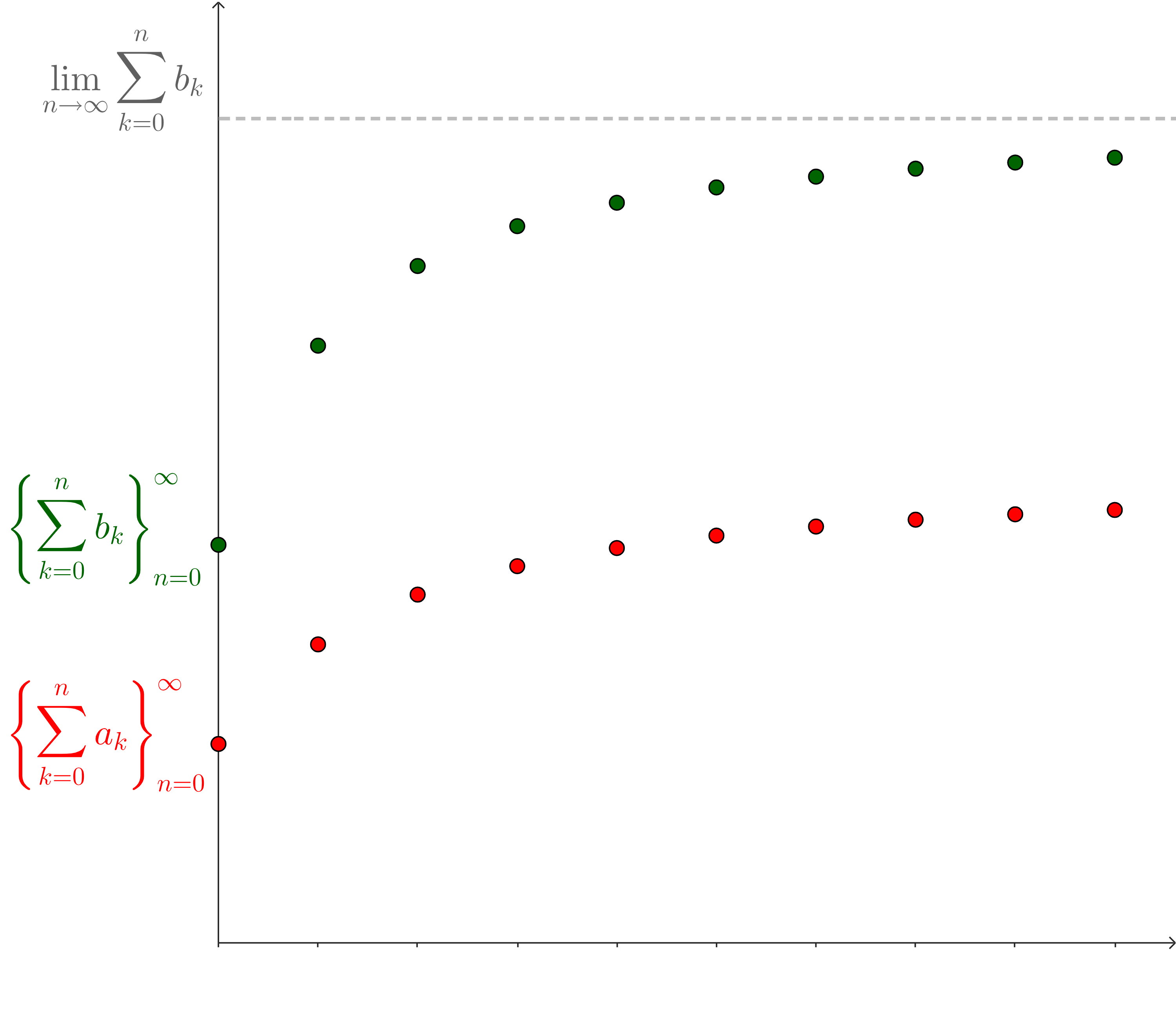

For our sequence of partial sums to be bounded, we originally had that our partial sums were smaller than an expression involving an integral. Then, those integrals eventually converged to something, and so our sequence of partial sums was bounded by a value.

Can we swap out an integral for a different partial sum? What has to happen in the limit to guarantee that our series converges?

Hint 2.

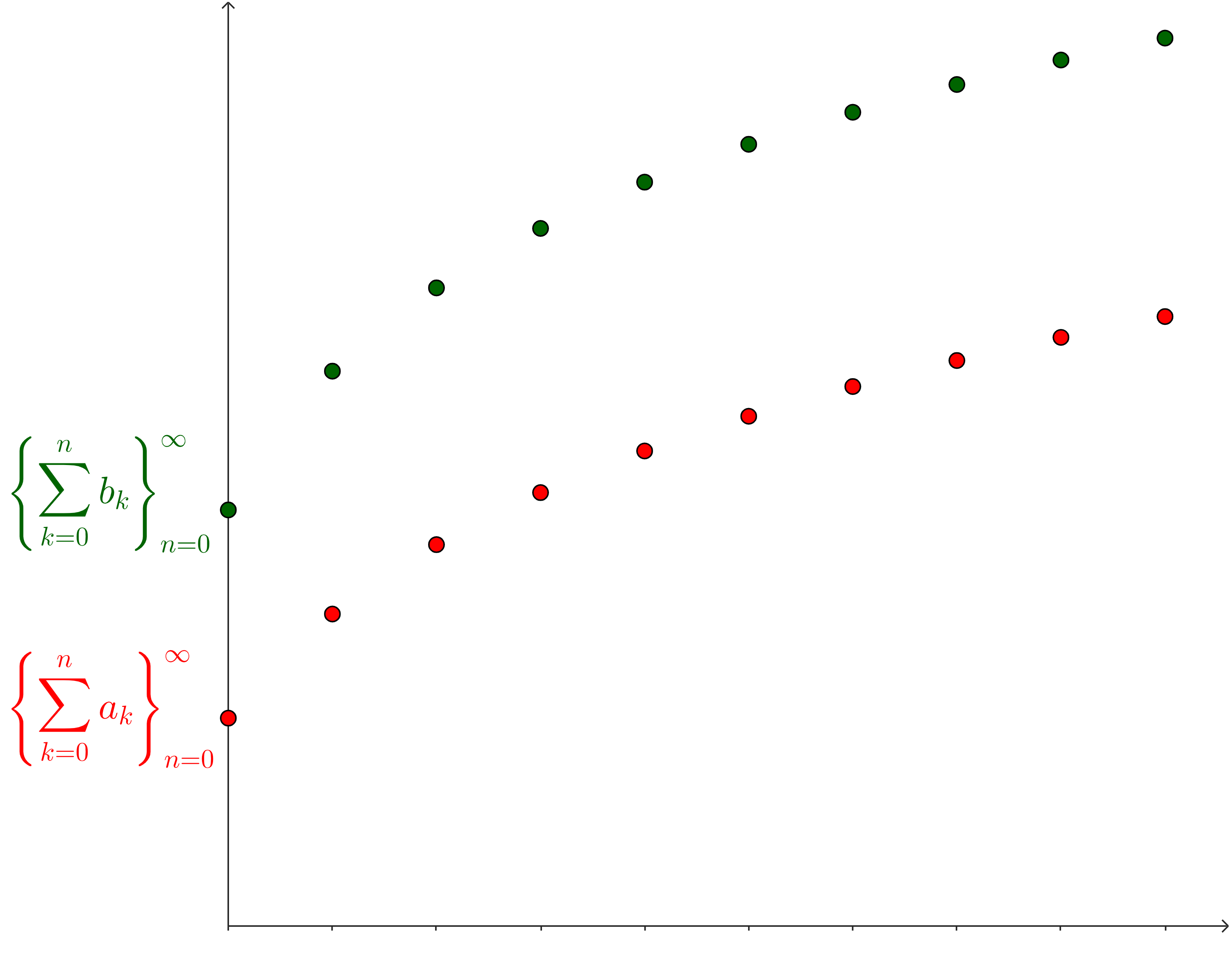

Similarly, when we showed that our partial sums were always greater than something involving an integral, then we were able to show that if that integral diverged, then our partial sums had no choice but to diverge to infinity as well.

What kind of partial sum do you need to change out the integral for?